There are 12 million deaf and hearing-impaired people in the UK. Take a moment to digest that sentence.

Twelve. Million.

What’s more, by 2035, it’s estimated that that figure will rise to 14.2 million. That’s a huge amount of people that could struggle to recognise a fire alarm. And being an invisible disability it can often be difficult to identify those in our buildings that may need assistance when it comes to an evacuation.

It could be easy to make the assumption that, because you can’t ‘see’ any hearing-impaired people in your building, there aren’t any there. Indeed, many hearing-impaired people don’t want to ask for assistance or specialist equipment and simply wish to go about their business.

It could be easy to make the assumption that, because you can’t ‘see’ any hearing-impaired people in your building, there aren’t any there. Indeed, many hearing-impaired people don’t want to ask for assistance or specialist equipment and simply wish to go about their business.

And it’s well documented that people who lose their hearing as they get older can take many years to accept that they have hearing loss, and it can take even longer for them to do anything about it. But hearing impairments don’t just affect older people. In the higher education sector, for example, hearing-impaired students can be reluctant to divulge information on their condition for fear of being misunderstood or being treated as ‘other’.

Between 2020 and 2021, there were 2.66 million students studying in UK higher education. Statistically speaking, around 133,000 of them will be hearing impaired. And in the hospitality sector, we know that there are many hotels across the UK that rely on manned evacuation processes and tags for guests to hang on their bedroom doors to identify them as hearing impaired, often leading to some scary and unnecessary problems.

How to wake deaf friends and not alienate people

Fiona, as mentioned in the interview.

Take Fiona Stewart, for example, who in 2015 had what many hearing-impaired people, sadly, view as a typical experience.

Staying at a hotel in Perth for a wedding, Fiona had a narrow escape when the fire alarm was triggered.

“The hotel’s fire alarm went off at seven in the morning,” Fiona told us during an interview back in 2016 “and I wasn’t evacuated. My parents got out of their room and were reassured that I was out of mine. Mum and Dad made their way to the meeting point in the hotel car park but it dawned on them that I wasn’t there. Mum told the manager and the firefighters that they had missed me, but the staff had informed them that everyone was accounted for.”

So how did this happen? Surely the hotel had a duty of care to ensure that, like all the other guests at the property, Fiona was suitably notified if she needed to evacuate?

“I tweeted the hotel two months before my booking to ask if they had any accessible fire alarms. They replied saying they had no equipment available. I’d hoped that in between my tweet and the date of my check-in, they would sort something out.” Fiona explained.

“Staff reiterated at check-in that they didn’t have anything to help. I explained that I would need to be notified in the event of a fire alarm and wrote it down on the check-in sheet. I explicitly stated that someone would have to come and get me if a fire alarm went off. The staff said that they had taken this on board.”

What happened next is nothing less than outrageous.

“The person who went to check my room claimed that he did open the door but didn’t see me as it was too dark. He also stated that he was distracted by other guests asking him for directions and advice. I suspect he opened the door and yelled “FIRE ALARM.” He also admitted that he didn’t flick the lights on and off as per the hotel’s procedures.”

As the remaining guests made their way to the muster point, the gut-wrenching realisation that Fiona was unaccounted for hit Fiona’s parents hard.

“My parents were very upset at this point, demanding my room was checked to see if I was there. Mum marched the manager and fireman to my room to see I was sleeping. It was rather unfortunate as I looked a mess and was drooling… but who cares? It was literally a matter of life and death. Or at least, it could have been. Luckily it was a false alarm. Someone had a shower and left the bathroom door open triggering the alarm with the steam.” Fiona continued “When it first happened, I was angry about how it impacted my family. Now, as I look back on it, I’m not angry anymore but I’m really worried that this could easily happen again or that it’ll be worse. Death could occur and that’d be horrendous for everyone involved. I don’t think hotels are really aware of what’s needed for deaf guests. It’s important to highlight that evacuation by hotel staff is not always the best answer. Deafness is an invisible disability. It’s not as if we have a giant neon sign flashing above us! Most people just don’t think about it and assume that we don’t need any support because we look physically able. Since this happened I’ve become a bit paranoid about fire safety. I often wake up in the middle of the night to put on my Cochlear Implant to check if the fire alarm is going off”

As shocking as Fiona’s experience was, it’s not unique. Rather than being an occasional blip in a business’s fire safety and evacuation strategy, this kind of manned evacuation process is very commonplace in hotels, showing at best a misunderstanding of, and at worst, a flagrant disregard for the Equality Act 2010.

Concerning the Equality Act

Sometimes still referred to as ‘The DDA’, the Equality Act 2010 sets out to ensure that everyone in the UK is treated the same way, and extends to things like making ‘reasonable adjustments’ for disabled people. This is a statutory requirement, so businesses should be putting measures in place as standard. If you’re waiting for a Deaf person to come into your building and announce their presence before considering their needs in an emergency, you could be breaking the law.

Sometimes still referred to as ‘The DDA’, the Equality Act 2010 sets out to ensure that everyone in the UK is treated the same way, and extends to things like making ‘reasonable adjustments’ for disabled people. This is a statutory requirement, so businesses should be putting measures in place as standard. If you’re waiting for a Deaf person to come into your building and announce their presence before considering their needs in an emergency, you could be breaking the law.

And this makes sense. We don’t, for example, wait until a wheelchair user wants to use a building before wheelchair access is designed into the building. And we don’t wait until someone injured themselves coming into the building before installing auto doors. The assumption is that these facilities are available as standard. But too often we see that adaptations for hearing-impaired people are an afterthought.

Considering people with hearing impairments outnumber wheelchair users in the UK by 12 to 1, do we focus more on mobility than sensory impairment, rather than giving them the equal consideration they deserve?

Applying the basics

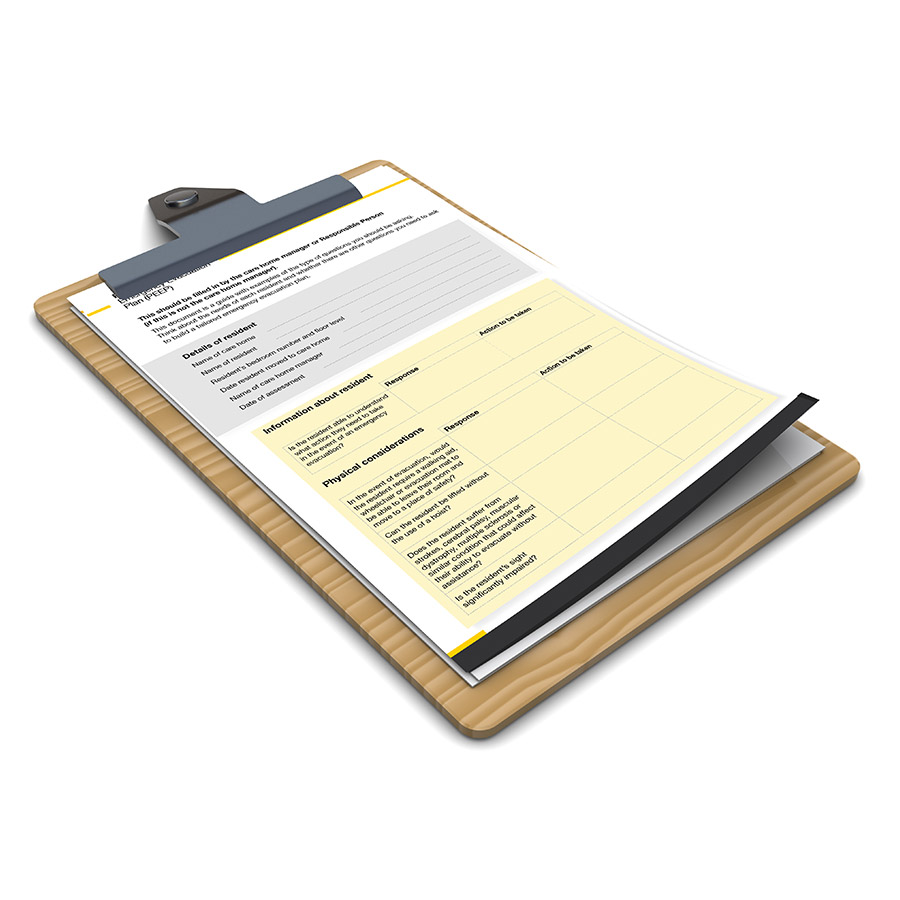

In certain situations, it’s much easier to identify those with hearing impairments and what requirements and adaptations they require. This is normally where you know that someone with a hearing impairment is regularly using a building. Where this is the case, Personal Emergency Evacuation Plans (PEEP) help to solve part of this problem, with an evacuation strategy tailored to each individual and giving the deaf or hearing-impaired person clear instructions on how to leave the building in an emergency.

with a hearing impairment is regularly using a building. Where this is the case, Personal Emergency Evacuation Plans (PEEP) help to solve part of this problem, with an evacuation strategy tailored to each individual and giving the deaf or hearing-impaired person clear instructions on how to leave the building in an emergency.

Often, a ‘buddy’ can be assigned to assist with this and ensure that the hearing-impaired person is evacuating. But the buddy system is only as reliable as the buddy. What happens if they call in sick or are not in the vicinity? Is there a chance that when that fight or flight response kicks in, the ‘buddy’ will forget or neglect their responsibility?

And again, PEEPs or the buddy system can only be applied where you know that they’re needed. They do very little for temporary visitors to premises like shopping malls, hospitals or public venues. Where the occupants of a premises are highly transient, it becomes difficult to know what measures or reasonable adjustments are suitable.

And bear in mind, this is just evacuating. You also have to be able to notify the hearing-impaired person that the fire alarm is actually sounding. This is where technology starts to come into play. A Fire Officer once laughed me off the phone at the mention of using an electronic means of alarm notification because ”Deaf people can still see.” This may be true, but people with hearing impairments often require (and, frankly, deserve) positive reinforcement in an emergency situation. They may be able to see that people are evacuating and possibly looking a bit frightened, but not knowing why can lead to further feelings of panic and fear. Asking them to rely just on what they can see going on around them could lead to negative behaviours and have deadly results.

Trust in tech?

There’s also a question as to whether or not we rely too much on induction loops. For many hearing-impaired people, they are a real lifeline. However, out of twelve million people, it’s estimated that only 2 million actually use a hearing aid, whereas nearly three times that many people would benefit from one. That still leaves millions of people that get no benefit from induction loops. At all. So whilst they’re vital for that group of hearing aid users, they may not be a wholly reliable way of notifying a majority of deaf and hearing-impaired people that a fire alarm is sounding.

An example of a Visual Alert Device.

So what technologies can we apply? It’s important to understand that when we suggest using tech to offer vital information to hearing-impaired people, we’re not suggesting that the methods discussed above should be replaced. Technology should be used alongside PEEPs and buddy systems to enhance evacuations. The more methods and provisions we have in place in order to enable people in our buildings to evacuate safely, the more lives we can save. Here are some common pieces of technology that are applied to assist with the notification and evacuation of hearing-impaired people;

Visual Alert Devices (VADs) or ‘beacons’ have been in play for years but are often used incorrectly. These devices should be installed throughout the entire premises for maximum impact. Deaf people don’t just linger in ‘key areas’ waiting for an alarm to go off.

Vibrating pillow pads are ideal for sleeping premises. They normally consist of a ‘base’ which reacts to the fire alarm. The ‘base’ sends a signal to a vibrating pad which can be placed under a pillow or mattress. These tactile signals should be strong enough to wake the hearing-impaired person, who will then see the visual alert device, normally built into the ‘base’, flashing.

Then there are pagers. Pagers are great. They’re robust and reliable. With the right signal boosters and site support, they can be installed in any location. But with this, comes a high price tag. Often prohibitively high. And whilst pager systems are often fully compliant with relevant guidance, pager handsets are often lost, out of battery or simply left at home. Often, these expensive systems are unused.

Fireco’s Digital Messaging Service.

If you can’t afford a pager system, you could look at using a cloud-based service or app that can send alerts in various formats to a computer or mobile device. These tend to be as reliable as, and more cost-effective to install and operate than, pager systems. And they’re much easier for hearing-impaired people, particularly younger people, to use. It’s possible that these types of systems can also be used by other people on site such as fire safety and security teams, or offered as a second stimulus for hearing people, helping to prevent inaction in the event of a fire alarm.

Understand the risks

In fairness, there are no ‘perfect’ provisions for fire notifications for the deaf and hearing impaired. There is a risk with all fire safety precautions. This is why it’s important to carry out the necessary risk assessments in conjunction with the hearing impaired, to identify what measures work best for each individual and each premises and to ensure compliance with the Equality Act 2010 and relevant fire safety legislation.

By not achieving this, you close your business to the £25bn annual spending power that the deaf community brings. Deaf and hard-of-hearing customers always go back to services that cater for their needs.

But above and beyond this, businesses have a corporate responsibility to ensure anyone using their building is safe. It’s the individuals responsible for fire safety that would be prosecuted should there be a failure to comply. Not the company. And with enforcement action published online for all to see, it could have an unhealthy effect on your business’s reputation.

How Fireco can help

Fireco can notify hearing-impaired people that they need to evacuate with our Digital Messaging Service and Deafgard vibrating pillow pads. Both have proven to be reliable assistive technologies used in various types of premises such as schools, hotels, universities, hospitals and public venues.

For more information and how we can help ensure that those 12 million hearing-impaired people in the UK are catered for in an emergency, call us on 01273 320650.

Complacency isn’t worth the trouble it brings. Don’t let fire safety fall on deaf ears.

Respected sir,

We Deal Electronic Fire Alarm on custom size and material for suitable requirements of customers. for any further details please contact us .

Landline: (021)35163641 / 42

Cell: 0331-8991733

easyautogates